There’s a new thing happening in Habit world…The Habit Portfolio has moved to Substack. The Habit Portfolio showcases original poetry, essays, and short stories by writers in The Habit Membership. New work is posted every Monday. You can subscribe here:

If you do writing or any other kind of creative work, you have to know what to do with criticism. Offering up a piece of writing feels a lot like offering up a piece of yourself, so “There are a few things wrong with this piece” can sound like “There are a few things wrong with you.”

Think of the strategies people use when dealing with personal criticism. Some of the less healthy strategies include defensiveness, self-loathing, and people-pleasing. Healthier strategies include listening, reflecting, and, when necessary, telling haters to back off. Because writing is so personal, writers can be tempted to go straight to those less healthy strategies when they receive writing feedback.

I find it helpful to try to think of my work as a writer the way a plumber thinks about his work as a plumber. Or, conversely, sometimes I try to imagine what it would be like if plumbers thought of their work the way writers think about theirs, as in the following skit:

HOMEOWNER

Could I speak to the plumber?PLUMBER

Speaking.HOMEOWNER

Yeah, hi. You worked on my bathroom sink faucet yesterday, and now it’s shooting water up to the ceiling.PLUMBER

That’s just your opinion.HOMEOWNER

No, it’s not just my opinion. I’m sloshing in water up to my ankles.PLUMBER

Maybe you should open up your mind. You seem pretty stuck on your pre-conceived notions of how a faucet ought to work.HOMEOWNER

I don’t think my mind is the problem here. Water is running down the hall. My kids are putting on their swimmies. I’m telling you, there’s something bad wrong with this faucet.PLUMBER

(After a long pause)

You know what? You’re right. There IS something wrong with the faucet. I am nothing but a big fraud.HOMEOWNER

I don’t know about that. I mean, the last time you came out, everything was fine. And the time before that. All I’m saying is that this particular faucet is shooting water up to the ceiling, and I need you to come fix it.PLUMBER

No. I quit. I’m not worthy to call myself a plumber. I’m going to become a writer instead.

A decent plumber—one who cares about his customers and about his work—would devote none of his energy to self-justification or self-loathing or self-anything-else. He would crank up the plumbing truck and go take care of the faucet. No matter how much pride a plumber takes in his work, he understands that he is not his work. If something is wrong, he wants to know so he can fix it.

I realize that the work of writing is quite a bit more personal than the work of plumbing. Nevertheless, you are not your work. You put a lot of your self into your writing. But, still, the writing is not you; it is something you make. That distinction is important for a number of reasons, not the least of which is that it gives you the critical distance you need to a) edit your work and b) assess and benefit from any critique you receive.

So now I’m going to ask you a personal question: why are you writing in the first place? If you are writing to express yourself or prove yourself or win respect or notoriety for yourself or for any other reason that includes the word self, it’s going to be that much harder to take criticism. As I said earlier, if you are writing for self, “There are a few things wrong with this piece” sounds like “There are a few things wrong with you.”

But if you write out of love—if you write because you love your reader and you love your material and you want to introduce them to one other—you will welcome well-informed criticism. Anybody who can help you connect with readers is an ally and a friend.

I said well-informed criticism. I suppose that’s where the real rub is. How do you know which criticism to take and which criticism to ignore?

If someone gives you advice about punctuation or grammar, that’s pretty easy. Go look it up and see if they’re right. Purdue University’s Online Writing Lab (OWL) is a great resource. I commend it to you.

But what about advice/criticism/feedback about style or organization or sentence structure or diction or, really, anything besides grammar and punctuation? There’s a lot of bad advice floating around out there. More to the point, there are a lot of people giving advice who know a few rules but have only a tenuous grasp on the big picture of how writing works. You may be in a writing group with one or two of these people. You might have quit your writing group because of one or two of these people.

To borrow some language from the counseling profession, you have to have a certain amount of yourself in order to know what writing advice to receive and what advice to reject. A while back I was talking to a person who told me that she had just finished writing a whole novel when somebody in her writing group told her she shouldn’t use the word that. So she went through and got rid of all the thats. But soon after she got through that ordeal, somebody told her that was ok to use that, and she shouldn’t have taken them all out. So now she was in the process of putting them all back in. “I get so much advice, how will I ever know I’m done?” she asked.

That writer doesn’t have enough of herself (or, one might say, enough of her voice) to know which advice to ignore. So she jumps right on whatever advice anybody offers. This isn’t going to end well.

My advice is to judge every bit of critique/advice/feedback in terms of connecting with the reader. If you were to implement a given piece of advice, can you see how it would help your reader understand your point better or enter more fully into your scene? Will it lower barriers between your reader and your material? If you don’t see how a given edit will make your reader’s life better, don’t be too quick to jump on it.

Having said that, let me also say this: if a reader doesn’t get what you’re trying to do, pay attention to that. The fact that you can explain yourself doesn’t count for much. It’s your job to communicate with your reader; it isn’t the reader’s job to figure things out. And before you say your reader/critic wasn’t paying close enough attention, allow me to remind you that they don’t owe you their attention. That’ something you have to earn.

Be aware that the great majority of writing errors come about not because the writer knows too little, but because the writer knows too much. Because you know exactly what you’re trying to say, your sentences will seem a little clearer to you than they will seem to the reader. So if it hurts your ego to acknowledge that a critic or writing partner is right, remember that one of the great gifts the critic brings to you is the gift of ignorance. She doesn’t already know what you’re trying to say.

It’s time for me to wrap this thing up, so let me say one last thing about critics. Just as there are writers who write for self-centered reasons, there are also critics who criticize for self-centered reasons. They like to hear themselves talk, or they like to show that they know more than you do, or they have hobby-horses they like to ride for reasons that are known only to them. This kind of critic may accidentally do you some good, but I wouldn’t take them too seriously if I were you.

But there are also plenty of people who offer criticism because they care about you or because they at least care about writing and they like to connect writers with readers and connect readers with good stories and ideas. These people are your allies. Stick to the closer than a brother. May the Lord bless them and keep them and make his face to shine upon them and give them peace.

Virtual Writing Rooms on Monday Tuesday, Thursday, and Friday

Tonight: Book Club—Dorothy and Jack (7pm Central)

Wednesday Afternoon: Habitation Poetry Group (Noon Central)

There's a place for you in this vibrant community of writers. Find out more about The Habit Membership here.

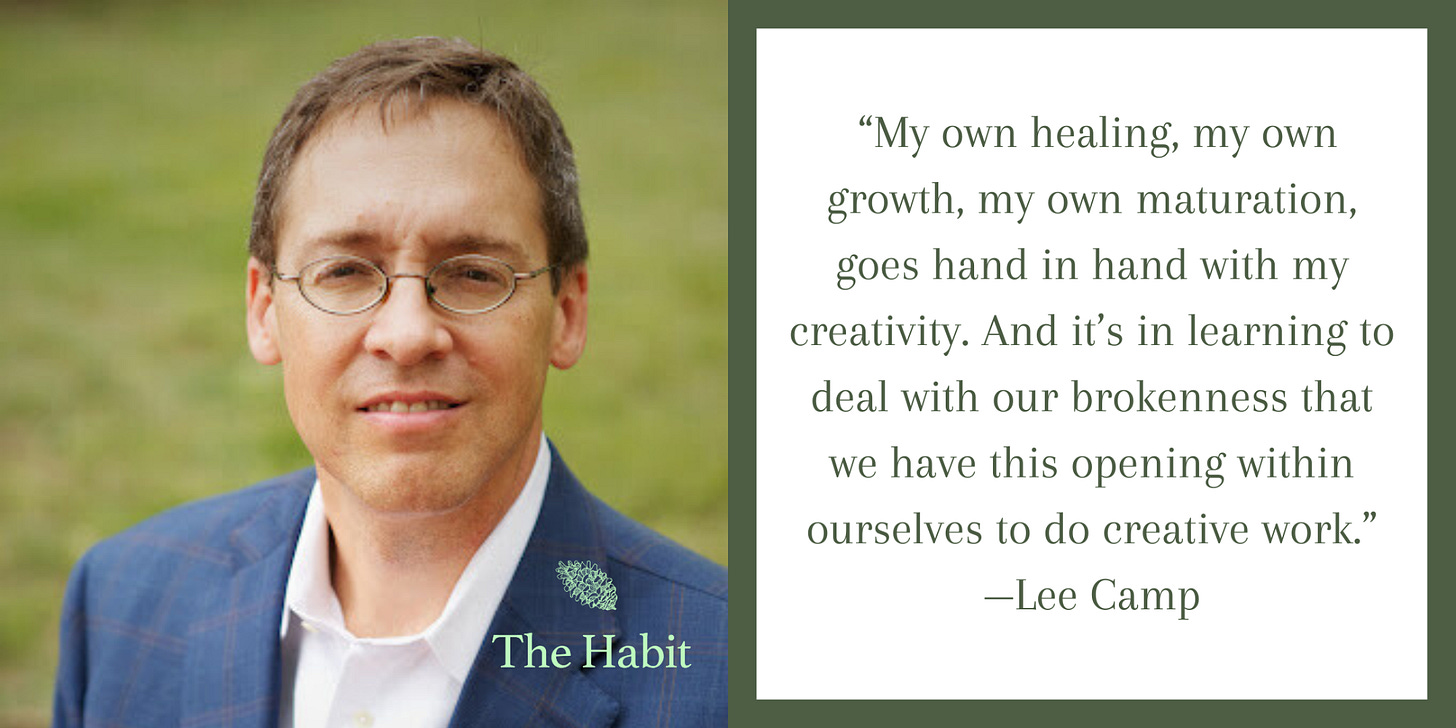

Lee Camp on The Good Life

Besides being an award-winning teacher and Professor of Theology & Ethics at Lipscomb University, Lee Camp hosts No Small Endeavor, a podcast that asks What does it mean to live a good life? What is true happiness? What are the habits, practices, and dispositions that facilitate human flourishing? Lee Camp explores these and similar questions with some of the most influential authors, scientists, artists, psychologists, philosophers, and theologians. I’ve known Lee a long time, so it was a particular pleasure to sit down with him for this conversation, in which we talk about ethics, virtue theory, and writerly habits.

This post was very timely for me. I have received the good news that a manuscript that I submitted several months ago is well received. In the near future I will get to read the feedback and constructive criticism from the publisher’s readers. I am thrilled that things are going so well and also preparing my stance concerning feedback, especially since the work included personal essays. Lessons on personal distance and framing needed changes in terms of better loving my future readers is just what I needed in this season.

This was a great post, Jonathan. You had me chuckling out loud with the whole plumber exchange. What a great way of showing a better and more healthy way of looking at criticism. And such wise advice on considering who our readers are and who we ultimately want them to be. I loved it all. Thank you, thank you. :)