Flannery O'Connor on Character-Driven Fiction

"A story is a dramatic event that involves a person because he is a person, and a particular person."

While putting things in place for this year’s edition of Short Story Summer Camp—which starts next Tuesday(!)—I revisited Flannery O’Connor’s essay, “On Writing Short Stories.” I was surprised to realize the extent to which my teaching of fiction has been shaped by one paragraph:

[I]n good stories, the characters are shown through the action and the action is controlled through the characters, and the result of this is meaning that derives from the whole presented experience. I myself prefer to say that a story is a dramatic event that involves a person because he is a person, and a particular person—that is, because he shares in the general human condition and in some specific human situation. A story always involves, in a dramatic way, the mystery of personality.

That’s as tight an explanation of character-driven fiction as you’ll ever see. In a sort of perpetual-motion machine, the action of the story reveals who the characters are, and who the characters are drives the action of the story. You have read stories, so you know how this works: When you start reading a story, you’re open to the possibility that the characters could do anything—or, rather, anything that is within the range of human possibility and psychology. As the story progresses, as you see what characters do, you have a clearer sense of what you can expect from any given character. Your very broad sense of what is possible (or believable) narrows as you get to know the characters. Characterization, you might say, is a matter of narrowing the range of believable actions for a character.

I don’t mean to suggest that things narrow down so far that characters have no choices: in good stories, characters always have choices, even when things happen to them that are out of their control. But to know a character (or an actual human being) is to have some sense of what they are likely and less likely to do in a given situation. People do surprising things (again, they are always able to make choices), but even surprise is a function of expectation: you have a sense of what to expect from a person, and that person does something else. There is a kind of surprising action that feels completely out of character (and therefore unbelievable), and there is a kind of surprising action that feels as if it reveals some new aspect of a character.

If you’ve ever written a story, you have experienced this movement from broader to narrower possibilities in characters’ action. I think this is what O’Connor means when she describes a story as “a dramatic event that involves a person because he is a person, and a particular person.” When you start writing a story, as when you start reading a story, anything can happen. Which is daunting to a writer. But once you make a few choices on your characters’ behalf, that impossibly broad plain of possibility begins to narrow into something more manageable: the characters start to tell you what might happen next. They can still surprise you—indeed, surprise is an outcome devoutly to be wished—but as your characters become particular persons, even their surprising actions live within a range of possibilities.

Things work this way in fiction because they work this way in real life. There is a range of actions that are believable for people in general, and there is a narrower range of actions that are believable for any particular person. If you told me that some woman pushed a child down in her haste to get on a bus, I would believe you. If you told me that my wife did that, I would find that very hard to believe.

The “rules” of fiction are never arbitrary rules. With few exceptions, you make sense of fiction in the same way you make sense of the rest of your life. We’ll be talking more about this kind of thing in Short Story Summer Camp, starting next week. I hope you can join us.

This year’s Short Story Summer Camp will run from June 24 through July 29. Together we’ll read and discuss short stories and write short stories of our own.

Each Tuesday I'll host a 90-minute Zoom lecture-discussion in which we'll examine the principles and techniques of the writers we've read for that week. Then, through weekly writing exercises and mutual feedback and discussion with your colleagues, you will apply those principles and methods to your own writing.

As usual, we’ll be running two simultaneous cohorts of Short Story Summer Camp: one for adults (age 19 and up), and one for students (age14-18).

You won't need to buy a textbook; I’ll provide online links to all the stories. Here are the readings:

ADULT COHORT:

“The Moron Factory” by George Saunders

“A Temporary Matter” by Jhumpa Lahiri

“The Faery Handbag” by Kelly Link

“Liars Don’t Qualify” by Junius Edwards

STUDENT COHORT:

“To Build a Fire” by Jack London

“The Third Wish” by Joan Aiken

“Jeeves and the Unbidden Guest” by P.G. Wodehouse

“Liars Don’t Qualify” by Junius Edwards

Dates and Times:

Tuesdays, June 24 - July 29

Adult Cohort: 1:00-2:30pm Central

Student Cohort: 3:00-4:30pm Central

(Lecture recordings will be available should you be unable to attend live.)

Cost: $119

This course is included in The Habit Membership. If you are already a member, you don't need to register. Members can find Short Story Summer Camp in the Habit forums. (Please note that The Habit Membership is limited to adults, age 19 and up.)

Virtual Writing Rooms on Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday and Friday

Wednesday at noon Central: Habitation Poetry Group

Thursday at 1pm Central: Office Hours

This week in The Habit Portfolio: “Return to the Sticks,” an essay by Sara Bannerman

There's a place for you in this vibrant community of writers. Find out more about The Habit Membership here.

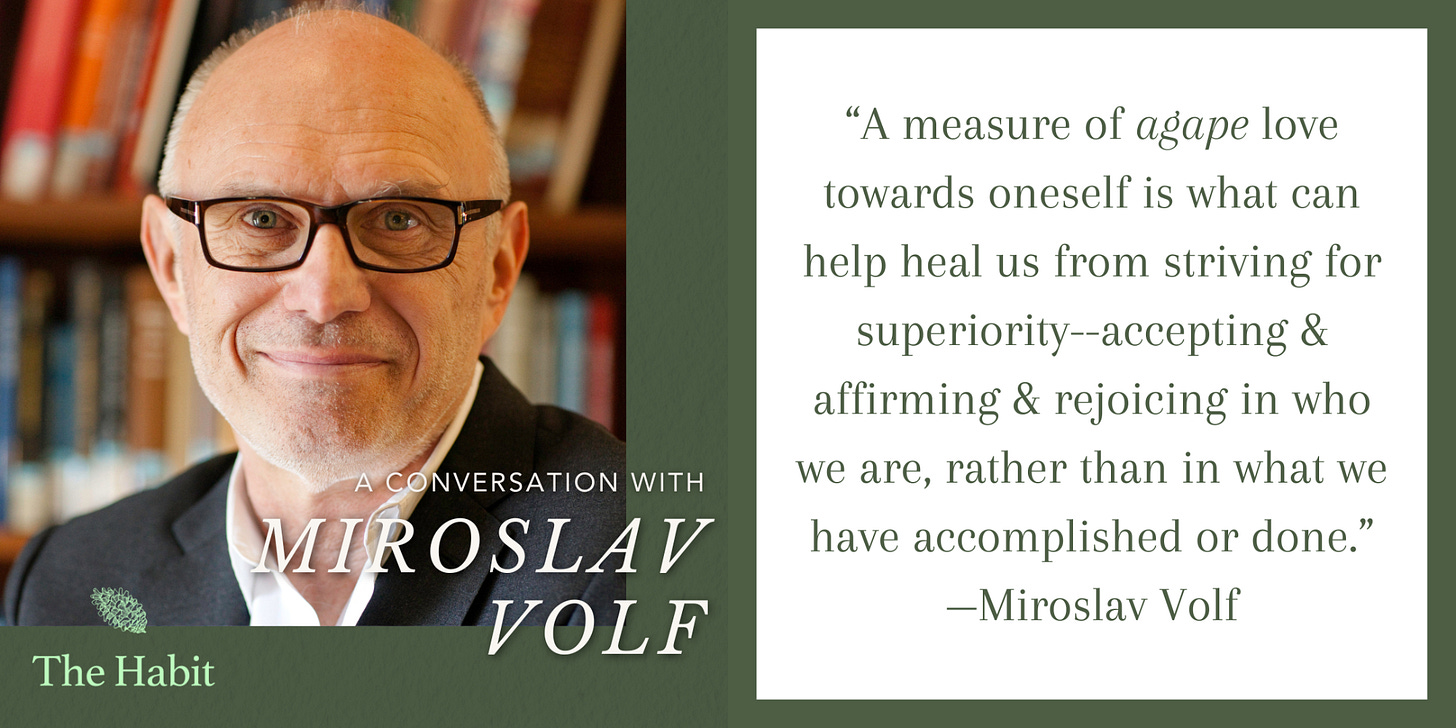

Miroslav Volf on The Cost of Ambition

Miroslav Volf is a theologian and professor at Yale Divinity School, where he is the founding director of the Yale Center for Faith and Culture. He is widely known for his work on reconciliation, forgiveness, and the intersection of faith and public life. He’s the author of at least twelve books, including the highly influential Exclusion and Embrace, as well as many articles and quite a few co-authored books. His most recent book is The Cost of Ambition: How Striving to Be Better than Others Makes Us Worse. In this episode, Dr. Volf and I talk about the difference between striving for excellence and striving for superiority. We talk about the freedom to be found when we stop defining ourselves in terms of our status relative to others. Also, we talk a good bit about Satan.

While it’s not believable that your wife would push down a child to get onto a bus, it’s totally believable that she would commit a surprise by trying to exit a train that is departing.

I just read that same essay the other night before you posted this, and I also noticed how your approach in The Habit has been shaped in some ways by FO. Even the concept of “habit” is brought up in many of her essays! I’m grateful for the work you do to support us, JR!